Guest blog for REDFeatherMind Body Spirit

Detail of the Moon card for the American Renaissance Tarot

Herman Melville’s short story, “The Apple-Tree Table; or, Original Spiritual Manifestations,” first appeared in Putnam’s Monthly Magazine in May of 1856. It’s certainly not one of Melville’s most famous stories, but I’ve chosen to discuss it here because it functions so well as an allegory of the spiritual “New Age” that dawned in mid-nineteenth-century America. My new publication with Schiffer/ Red Feather, the American Renaissance Tarot, provides a detailed look at this largely unknown and deeply fascinating history through the stories told by America’s most iconic writers.

One of the first things that happens in “The Apple-Tree Table” is that the narrator finds a rusty key that belongs to a locked attic room in a “very old house” in “one of the oldest towns in America.” While the narrator has shown no previous interest in the garret, the possession of a key stokes his curiosity, and also piques the reader’s attention around what colonial-era secrets the garret might hold.

Rather shockingly, the garret appears to have been the den of an early American alchemist or ceremonial magician! Melville tells us that “broken, be-crusted, old purple vials and flasks” were set out on “the satanic-looking little old table” for which the story is named. The narrator imagines “a whole conclave of conjurors” to have inhabited the apartment, and fantasizes that a Faustian bargain was here made with the “Evil One.” When I first read this story about twenty years ago, I thought Melville’s gothic machinery was a little absurd. There were no early American alchemists or magicians. It beggars belief that anything so interesting could have happened in the very old New England town described in the story.

But it turns out that I was dead wrong about that. Walter Woodward’s Prospero’s America details the life of a colonial governor who was not only an alchemist, but also a Rosicrucian seeker who emulated the career of the wizard John Dee, court astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I. Puritan libraries were well-stocked with magical treatises like Cornelius Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Beyond New England, the magical scene was even more experimental, with German Pietists carting the mystico-alchemical treatises (and beliefs) of the theosophist, Jacob Boehme, with them to the mid-Atlantic colonies.

I’m not sure how much of this history Melville knew when he wrote “The Apple-Tree Table.” One of the themes of the American Renaissance Tarot is the uncanny power of literature to shape the future, so in that sense it doesn’t matter if Melville knew he was writing an allegory about America’s hidden magical lineage being “reborn” in the 1850s. What Melville was consciously doing, however, was drawing a parallel to the Salem witch hysteria of the 1690s and the Spiritualism craze of the mid-nineteenth century. He was not the first to note that both movements had been fomented by teenage girls.

Cotton Mather, who has long been demonized as both an enthusiastic investigator of the witches at Salem and an advocate of their executions, was once a very respected polymath and theologian. The narrator of “The Apple-Tree Table” discovers a copy of Mathers’ Magnalia Christi Americana in the spooky old garret, and takes to reading it late at night, after the rest of his family has gone to bed. What unnerves our nineteenth-century narrator most is Mather’s unshakable belief in the Devil, and the witches who carried out his work. Nineteenth-century Christianity, by contrast, had become both more reasonable and more inviting, with concepts like Hell and original sin taking a backseat to more popular ideas like free grace and the inherent goodness of the human spirit (these developments are told in the Star and Pope cards of the American Renaissance Tarot). Paradoxically, this literary time-travel back to the pious Puritan era conjures up all the witches and evil spirits that had been quieted by the progress of American Enlightenment.

“The Apple-Tree Table’s” narrator has two teen daughters whom he is quick to point out are not the “Fox girls,” the two young women, Katie and Margaret Fox, responsible for instigating the national obsession with Spiritualism in 1848. Yet we are surely meant to think of the Fox sisters when the narrator’s daughters, Anna and Julia, create a ruckus over the cloven-footed table that the narrator has rescued from the alchemist’s attic and placed in the parlor.

Kate and Maggie Fox, the sisters behind the popular religion of Spiritualism.

The table starts behaving unaccountably, making an awful ticking noise that causes the narrator’s hair to stand on end. “Could Cotton Mather speak true? Were there spirits? And would spirits haunt a tea-table?” Melville’s use of the table as the source of “original spiritual manifestations” is a reference to the seance culture made popular by the Fox sisters, which often involved groups of people seated around a table as they attempted to make contact with the spirit world. Before the innovation of the ouija board, spirit communication proceeded by raps and knocks on tables (or walls) and was then translated using an alphabetic code. Sisters Anna and Julia become hysterical and shriek “Spirits! Spirits!” at the haunted table.

Melville’s epistemological sophistication is shown by the story’s clever ending, which offers a spectrum of responses to the wonder that unfolds around the haunted table. Ultimately two bugs hatch out of the 150-year-old wood of the apple-tree table, having been stirred into life by the heat of the narrator’s tea-pot. The narrator’s wife, whom he calls “Mrs. Democritus,” is confirmed in her empirical attitude and disbelief in spirits, and vows to have the table rubbed with roach powder. The narrator’s daughters, on the other hand, are utterly charmed by the magic of the prodigy. Together the family watches as a beautiful bug chews its way out of the old wood, “a bug like a sparkle of a glorious sunset.” Though they listen to the dubious scientific explanation for the miracle offered by a naturalist, Anna and Julia prefer the magical worldview: “‘Say what you will, if this beauteous creature be not a spirit, it yet teaches a spiritual lesson … Spirits! Spirits! … I still believe in them with delight, when before I but thought of them with terror.’”

There is perhaps no more succinct way to express the sea change that came over mid-nineteenth century America than Julia’s dialogue, above, which articulates the mass transition from terror to wonder regarding the existence of spirits in the hearts of many Americans. Spiritualism brought comfort to families in a period with high child mortality rates, and also offered women positions of spiritual authority that were not available to them in conventional churches. Historians of the occult look to Helena Blavatsky’s 1877 text, Isis Unveiled, as the official beginning of the “occult revival” that we are very much still in. But the movement Blavatsky founded, Theosophy, coalesced out of her Spiritualistic investigations, and she believed the Fox sisters were harbingers of the new spiritual dispensation.

The story of Spiritualism and the Fox sisters is told briefly in the chapter for the Moon card of the American Renaissance Tarot, but in truth their story represents just one “leaf” of the 78-page “book” we call the Tarot. There are cards devoted to goddess worship, nature religion, mental magic, rootwork, Rosicrucianism, Freemasonry, Unitarianism, sex magick, pantheism, and other examples of the spiritual alternatives that together make up the patchwork quilt of American Metaphysical Religion. You might draw the Moon card and fall down the rabbit-hole of the Fox sisters’ controversial legacy, but that is only one of many portals the American Renaissance Tarot opens up into American religious history, which has always been radically experimental.

I noticed (with a little shiver down my spine) that Melville in his 1856 story looks back roughly 165 years to the witch panic at Salem, while I am looking back 165 years to “The Apple-Tree Table” today. Mass interest in spirituality happens in cycles, and we are at the peak of one now. But perhaps you, reading this, resemble the narrator of Herman Melville’s “The Apple-Tree Table,” who vacillates between the empiricism of his wife and the blind belief of his daughters. Perhaps you are sort of a “Democritus by day and Cotton Mather by night” as he reveals himself to be in the story. The genius of Melville’s equivocal voice is that most of us find ourselves in this very middle, or muddle, of wanting to identify as sensible, rational humans, at the same time that we desperately crave for wonder and spiritual meaning. The American Renaissance Tarot can be your key to the locked garret of our spiritual history, but you get to be the decider of what speaks to your heart, and what’s a “humbug” (and yes, Melville tells us that the beautiful bug of “The Apple-Tree Table” had something of a hum to it!) The humor and humility that Melville always brings to questions of faith are in top form in this charming story; I encourage you to read it to catch a reflection of the present in the mirror of the past.

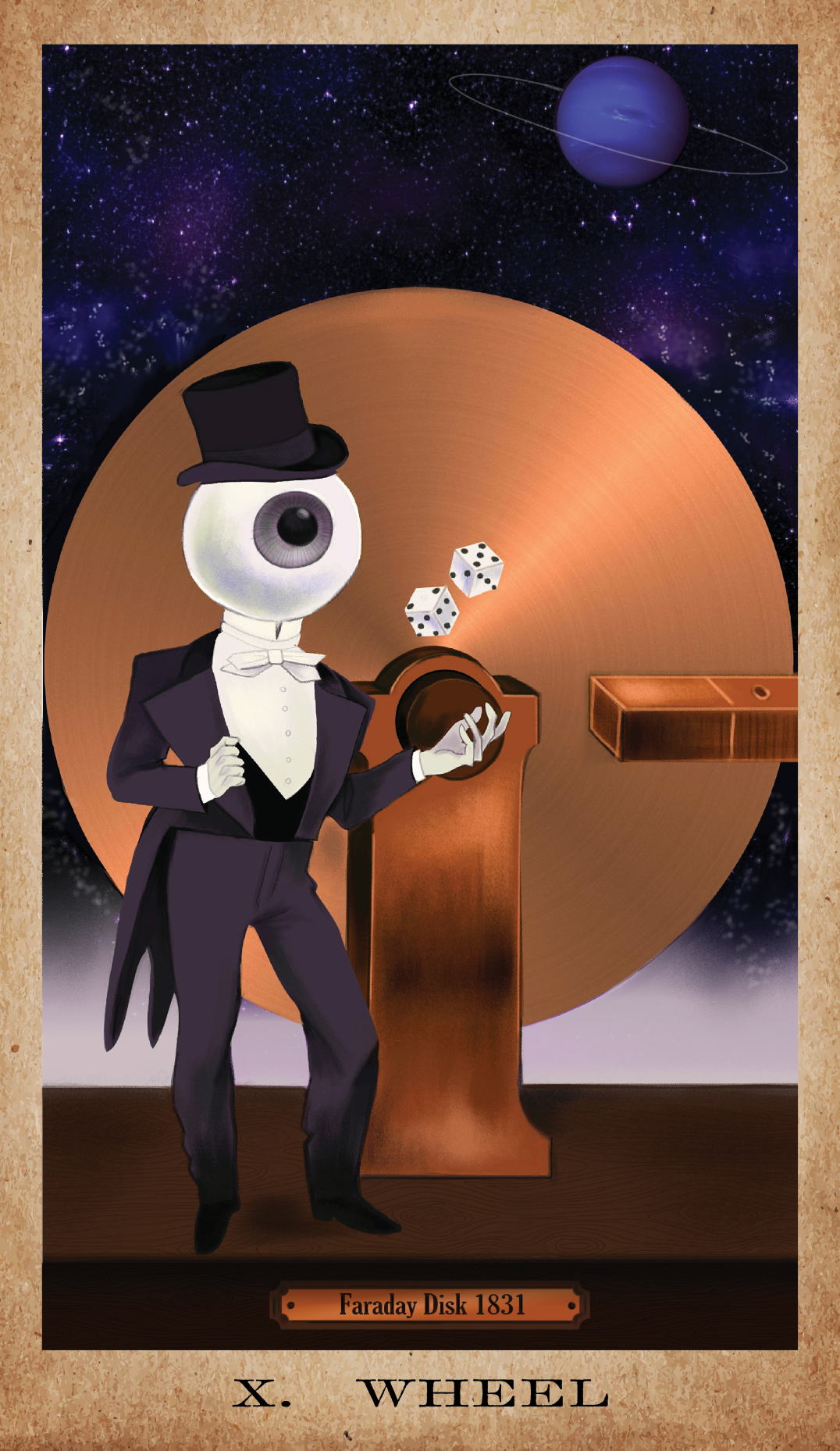

Our Wheel of Fortune card sneaks in a little ode to Neptune, which was discovered during the broader American Renaissance period in 1846. Neptune’s 165-year orbit marks periods of spiritual renewal, as discussed above.