Pamela Colman Smith: American

Pamela Colman “Pixie” Smith circa 1912

A blog inspired by the new biography of Pamela Colman Smith, illustrator of the iconic Rider-Waite Tarot. I delve deep into Smith’s elite American ancestry, and detail how her performances as an Afro-Jamaican story-teller have led to the persistent myth that she was a black woman. This complicated history of colonial privilege and racial appropriation speaks to the fundamental Americanness of Pamela Colman Smith.

Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story

OK yes, calling Pamela Colman “Pixie” Smith an American is contentious, given that she was born in London and died in Cornwall, and was also - great heavens! - a Catholic. But I have a lot of supporting evidence to back up my claim that she can be usefully understood as an American artist. Pamela Colman Smith, whom I sometimes refer to as “Pixie” for clarity, is most famous for illustrating the Rider-Waite Tarot deck that was first published in 1909. She was directed to create the images by occultist Arthur Edward Waite, and their iconic collaboration has retained the names of its publisher and originator (Rider and Waite, respectively) while eliding Smith’s artistic contribution. As a corrective, many people now refer to this deck as the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, a practice I follow; from here on out I will use the acronym RWS for this Tarot.

Iconic image from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot that dates to 1909

Love it or hate it, the RWS Tarot defines what most people think of whenever the subject of Tarot cards comes up. Non-specialists may not be aware that the RWS had many historical predecessors and some noble competitors in its day. For the reason of its mass popularity alone, the RWS Tarot merits our interest and respect. When I was picking out an artist for The American Renaissance Tarot, I had Pixie’s straightforward illustrations strongly in mind. The modern trend in Tarot seems to be heavily embroidered fantasy-scapes, and yet Pixie’s bold outlines of figures in theatrical poses, set against two-dimensional backdrops, conveys the Tarot’s archetypes in a decidedly pure and direct manner.

I never knew much about Pixie except that she was British and had died in obscurity; she never realized any financial security or status from illustrating one of the most popular items of printed ephemera in the world. This is largely due to the fact that the RWS Tarot was not widely distributed until circa 1970 when it was acquired by Stuart Kaplan of U.S. Games Systems, twenty years after Pixie’s death in 1951. In my news-feed last fall, I saw Tarot maven Mary Greer mention that she had collaborated on an in-depth biography of Pixie with Kaplan and some other writers. “Why not?” I thought. “Why not learn about one of the most influential artists in the Tarot tradition?”

“The Blue Cat" by Pamela Colman Smith, 1907, courtesy of Mary Greer

I ordered online, and because of what I paid for the book, I was expecting a flimsy paperback with an insert of illustrations. I’m kind of a scholarly book junkie, so it’s not unusual for me to lay down $50 on a 200-page treatise. When Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story arrived at my door, I gasped. I may have cried. I wasn’t expecting this 4-pound, 8 by 10 hardbound art book with beautiful illustrations on almost every page. In a 400-page book, that’s no small feature! For the research that went into this volume alone, U.S. Games should be charging triple. It is clearly a labor of love on behalf of the authors; my first thought upon opening the book was “no one made any money on this.” I immediately bought a second copy for Celeste, the artist for The American Renaissance Tarot, and she had a similar SQUEEEE reaction. Even if you’re not a fan of the RWS Tarot art, Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story provides a unique window into the artistic development of an early 20th-century esotericist. Like Arthur Edward Waite, Smith was a member of the Golden Dawn, and many of her works beckon the viewer into other worlds; the art that appears in this biography reveals a texture and depth not apparent in the mass-produced Tarot cards.

Pixie Smith, American Elite

I tore through Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story in about a day and a half, and though the book is full of gems related to the creation of the RWS Tarot and Pixie’s impressive literary contacts in England (like William Butler Yeats and Bram Stoker), I never really got over the startling fact of her American education and lineage. OK, now why would that matter? Aren’t we all citizens of the world? Can’t we say a savant like Pixie transcends petty limitations like national identification? Sure - but then we lose a lot as far as contextualizing her in her times. I remember first encountering this issue when I was an undergraduate English major conducting an independent research project on Anais Nin. Nin was the daughter of a Cuban father and a French mother and was raised in Spain, then lived much of her adult life in France, but wrote and published in English - could I really get away with calling her an “American” writer just because she spent her final decades in Silverlake? And what were the stakes of identifying her as an American?

The issue of nationality is actually a much more prevalent one than you might imagine in academic circles. The reason for this is that we’re asked to specialize - will you become an expert in English or American literature? Because you can’t very well do both. Turncoats like T.S. Eliot and Henry James, prominent writers who were born and raised in America but who later became British subjects, cause particular problems in academia, because specialists in both fields can claim them. If your eyes are glazing over right now because you imagine that there are no fundamental differences between the British and American literary traditions, well - that’s a common misconception that The American Renaissance Tarot was conceived to address!

American author Nathaniel Hawthorne was so haunted by his colonial ancestry that it became a recurring theme in his work. His great-great-grandfather John Hathorne was a hanging judge at the infamous Salem Witch Trials, and Hawthorne felt the wrong of that legacy acutely. Pictured here is our ode to Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, the Five of Cups for The American Renaissance Tarot.

Full disclosure: I enrolled in graduate school in English in part because as an undergrad I had watched a particularly terrifying old professor thunder out Puritan sermons in my early American lit class. In many ways, it was a terrible class - “terrible” in the sense that the thematic content of the course was sin and hellfire and Satan roasting you over the pit. The material wasn’t especially literary (no belles-lettres here), and the syllabus was packed with “dead white guys.” One of those dead white guys was Thomas Hooker (1586-1647), founder of the Connecticut colony, whose vision of a representative government would later influence the writing of the U.S. Constitution. Pamela Colman “Pixie” Smith is a direct descendant of Thomas Hooker.

Now, don’t worry, I’m not going to claim Pixie’s “Americanness” based on one moldy old relative. But it does bear mentioning that Hooker, by virtue of his primacy in the colonies, ranks among the closest thing Americans have to “royalty.” Other notables in the direct line of descent from Hooker are Aaron Burr, William Howard Taft, and J.P. Morgan - you know, nobodies like that. If you have an ancestor written up in Cotton Mather’s magisterial Magnalia Christi Americana, as Pixie did, you’re no ordinary American - you’re a Boston Brahmin.

Pixie’s paternal grandmother was a Hooker (it’s a joke that never really gets old - unless of course you are a Hooker), now let’s look at her paternal grandfather, the Smith side. No big deal, Cyrus Porter Smith was just mayor of Brooklyn, then a New York state senator, and, to quote from Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, “[Cyrus Porter Smith was] a prosperous businessman, he helped found the first gas company in Brooklyn, was director of Brooklyn’s Union Ferry Company, president of the Brooklyn City Railroad Company and one of the founding directors of Brooklyn City Hospital” (16). OK, now all of that “citizen of the world” stuff aside, if you come from a family that is heavily involved in American politics, industry, and infrastructure, as Pixie did, you’re more American than most. The first Smith on that side of her family arrived in the colonies in the 1630s, and another direct relative in the Smith line was purportedly felled by witchcraft - that crazy fad that spread through New England in the late 17th century. So again we see a theme in Pixie Smith’s ancestry of not just Americanness, but of preeminent Americanness.

Alright, what about Pixie’s mother’s side? Her ancestor on her maternal grandmother’s side, Edmund Chandler, arrived in Plymouth about 1629, making him one of the first few thousand residents of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He was also part of the Puritan Separatist community at Leiden, and, if you’re an American history geek like me, you know it’s hard to get more original in your Americanness than to have been one of the Leiden Separatists! I remember standing tearfully, in Leiden, looking over a canal that was marked with a plaque stating that this was the site where the Pilgrims had first embarked from exile in Holland en route to their new home in America. More on Pixie’s maternal grandmother, Pamelia Chandler Colman, in a minute (the prevalence of Pamela’s and Pamelia’s in this family has led me to favor the term “Pixie” to distinguish the RWS Tarot illustrator).

“Hooker and Company Journeying Through the Wilderness from Plymouth to Hartford, in 1636,” by Frederic Edwin Church, 1846. Colonial founder Thomas Hooker was Pamela Colman Smith’s 6x-great-grandfather.

Pixie’s maternal grandfather’s side, the Colman side, boasts an ancestor in the direct line who arrived in Boston in 1635, putting him in elite company with the first few thousand colonists in the Massachusetts Bay. It’s unusual, to say the least, that Pixie’s ancestry is so marked by the distinguished “first families” of America, unless of course hers was a lineage with an interest in only uniting with other prominent families, which it appears to be. Far more common are pedigrees like mine: while I have a distinguished early American ancestor or two, the majority of my British ancestors were of the Scots-Irish servant class who came to the colonies in droves in the 18th century. To put a really fine point on it, the waves of Scots-Irish immigrants are often linked to the formation of the class colloquially known as “white trash.” If we investigate this term, we find that it simply refers to “poor people.” Pixie Smith’s family was the opposite of “white trash.” In spite of the aggressive and persistent myth that the United States is a class-free nation, there has always been an American elite, and Pixie Smith was its scion. Her family lineage is about the closest you can come to being “titled” in a country which denies it has an aristocracy.

Though her family lineage is only one aspect of Pixie’s Americanness, it’s useful to remember that her family was not American by only a generation or two, but rather was comprised of American founders dating back the full 250-year length of American history at the time of her birth. This fact adds interest to her choice to settle in Great Britain after her artistic education in New York. (The outline of the above genealogy appears on pages 15-16 of Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, more detailed information was gleaned from this online genealogy.)

Lest you think I’m some chest-pounding nationalist, I’ll remind you that it’s common in America to distinguish 2nd and even 3rd generation immigrants by their nation of origin, e.g. “Japanese-American” or “Mexican-American,” as if one cannot become purely American in the space of a single generation. Applying the same logic in reverse, it’s odd that we imagine that the scion of an old American family is cleansed of all her Americanness simply by virtue of having been born in London. It’s odd but not rare, because Americans are almost completely ignorant of the fact that they have a culture; non-Americans are often painfully aware of American identity, yet born Americans seem to only discover their uniqueness when they travel abroad. Pixie Smith’s Colman ancestors, however, were actively engaged in establishing the character of American art and letters in the nation’s early period.

The Colman family and the American Renaissance

For this section, it’s useful to keep in mind what Pamela Colman “Pixie” Smith’s particular legacy to the Tarot tradition was, according to Arthur Edward Waite and many other commentators. Here I quote from the Encyclopedia of Tarot, Volume III, by Stuart Kaplan; this selection appears on the product page for the Rider-Waite Tarot on the U.S. Games Systems website:

“A unique feature of the Rider-Waite deck, and one of the principal reasons for its enduring popularity, is that all of the cards, including the Minor Arcana, depict full scenes with figures and symbols. Prior to the Rider-Waite Tarot, the pip cards of almost all tarot decks were marked only with the arrangement of the suit signs - swords, wands, cups, and coins, or pentacles. The pictorial images on all the cards allow interpretations without the need to repeatedly consult explanatory text. The innovative Minor Arcana, and Pamela Colman Smith's ability to capture the subtleties of emotion and experience have made the Rider-Waite Tarot a model for the designs of many tarot packs."

To paraphrase, Pixie Smith improved and/or simplified the use of Tarot cards by adding engaging illustrations to a tradition that had previously relied heavily on abstract symbolism (numbers and objects). The Colman side of Pixie’s family figures strongly in the history of American illustration and art.

The Emperor for The American Renaissance Tarot, inspired by Longfellow’s Hyperion, a book published by Pamela Colman Smith’s grandfather.

Pixie’s grandfather, Samuel Colman (1799-1865) was a prolific American publisher based in New York City. Colman “made a mission of publishing American authors” (Sarah Wadsworth, In the Company of Books, 2006), and he even attempted a literary magazine, the short-lived Colman’s Monthly Miscellany, in 1839. Samuel Colman’s name was familiar to me because he was the publisher who put out Longfellow’s early work, Hyperion, in 1839, a fiction drawn from Longfellow’s period of language study in Germany. Hyperion and its romance of Heidelberg were the inspiration for the Emperor card in The American Renaissance Tarot.

While none of these facts may seem significant in themselves, the era of Samuel Colman’s activity makes them so. The 1830s and 1840s marked a new period of American self-awareness, with an accompanying hunger for a national literature, that simply did not exist previously. Ralph Waldo Emerson penned his philosophical essay, Nature, in 1836, which would became the representative text of the first truly original American literary movement, Transcendentalism. In 1837, Emerson delivered the lecture “The American Scholar,” which called for Americans to throw off their slavishness to European models, and to discover their own authentic forms. In the antebellum period, the idea that a nation of upstart farmers could make meaningful contributions to literary culture still seemed edgy - even preposterous. Sydney Smith had asked in the Edinburgh Review in 1820, “Who reads an American book”? to much snickering acclaim; in the succeeding decades, a bold set of authors and publishers delivered replies to Smith’s jab in the form of original American works.

Poets of America: Illustrated by one of her Painters, edited by John Keese and published by Pamela Colman Smith’s grandfather Samuel Colman. Image courtesy of AbeBooks.com

Samuel Colman’s most important publication is probably Poets of America: Illustrated By One of Her Painters (1840). Compiled by editor and auctioneer John Keese, Poets of America was an attempt to capitalize upon the new enthusiasm for native bards. Though similar anthologies had appeared throughout the previous decade, Poets of America had this unique feature: it was illustrated. Samuel Colman has the distinction of being the first American publisher to join image to verse (Henry Tuckerman, Book of the Artists, 1867). The most enduring poetry anthology of the times, Poets and Poetry of America, compiled by Edgar Allan Poe’s nemesis Rufus Griswold, appeared a few years later, yet Colman’s various poetry anthologies were advertised steadily through the 1840s. They appear to take the form of “gift books” or presentation volumes, fancy editions that were more notable for their art than for their letters. Colman’s was also one of the first publishing houses to produce color illustrations, quite a technological feat in those days (The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Vol. VII, 1897).

Pixie Smith’s grandfather Samuel Colman was a publisher known for interpolating image into text, presumably for the purpose of adding value to American literature as a commodity. This endeavor was very much a family business. Samuel’s wife, Pamela Chandler (1799-1865), and daughter, Pamela Atkins (1824-1900), both produced copious content for his publishing house, writing as Mrs. Colman and Miss Colman, respectively. Many of these volumes were for children. (Note: Pamela Atkins Colman was Pixie’s aunt, not her mother). All members of the family seemed to wear many hats, working variously as editors, compilers, writers, illustrators, and engravers. This online article in the Blake quarterly magazine takes a detailed look at Mrs. Colman’s many roles in publishing an illustrated edition of Blake’s poems intended for children.

Adding to the repetition of family names is Samuel Colman (1832-1920) the younger, Pixie’s uncle, who grew up amidst the highly cultured space of his father’s publishing house and book shop. Samuel Jr.’s later success as a landscape painter in the Hudson River style means that there are many biographical accounts of this notable American. As I combed through blurbs about the younger Samuel to glean more information about the father, I noticed something odd. It didn’t seem possible that Samuel Colman, Sr. could specialize in so many fields; from the 1830s through the 1850s he was described as being a publisher, book-seller, engraver, art-dealer, framer, and antiquarian, and his New York rooms were described as everything from curiosity shop to art supply store, and as both gallery and literary salon!

Light fell on the confusion from a more nuanced entry in The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Vol. VII (1897). It turns out that Samuel’s father, Samuel Sr., was the publisher and engraver, while his uncle William Colman was the proprietor of a book shop and art gallery on Broadway. Both men kept rooms in New York, but uncle William’s were a New York City landmark. Colman’s curiosity shop seems to have been an extraordinary place, both for viewing art and for viewing the elite class of artists and writers who patronized it. It’s been a challenge to whittle down descriptions of Colman’s shop to a few historical accounts for this article, since his gallery of oil paintings and fine prints was such a popular stopping place for New York City flâneurs. The most iconic story about Colman’s shop concerns its key role at the beginning of America’s first original artistic movement. Thomas Cole (1801-1848) exhibited his paintings of the Hudson River Valley in Colman’s shop windows in 1825, and a new school of American landscape painting was born. For the first time, American painters celebrated American subjects and their own native scenery instead of being bound by European models and scenes.

One of the paintings that Thomas Cole displayed in William Colman’s shop window in 1825, Lake with Dead Trees, which launched an original movement in American art.

Pixie Smith’s grandfather, Samuel Colman, and great-uncle, William Colman, both supported the development of uniquely American forms in literature and the visual arts with their respective endeavors. William’s shop was originally called “Colman’s Literary Rooms” and held salons; Samuel the publisher also sold fine engravings. William Colman “opened the first gallery in the city for the sale of pictures” in 1844, making him a significant figure in the history of the New York art world (The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Vol. VII, 1897). Thus it appears that Pixie’s Colman ancestors were as active in fostering the fine arts and culture of America, as her Smith grandfather was in laying down the infrastructure of Brooklyn.

Book label from William Colman’s shop. For image source and more on the legendary book shop, click here.

As someone with a passion for both Tarot history and the American Renaissance, it’s great fun to see my obscure interests come together in this surprising way. I also have a fascination with the history of urban culture, its coffee-houses and cafés and two-bit attractions, and Colman’s shop seems like a crown jewel of antebellum New York. Reading between the lines in the following write-up from The Southern Literary Messenger (1850), Colman’s Fine Art Emporium comes across as a Barnum’s museum of a book shop, with taxidermy two-headed cows nestled between shelves of moldering medieval grimoires, and jagged crystals competing with fine sculpted busts for the rubes’ attention:

“I must not forget to notice the breaking up of the old ‘Curiosity Shop’ on Broadway, long known as the Emporium of the Fine Arts, under the auspices of that eccentric and indefatigable virtuoso, the late William A. Colman. He had been devoted to the collection of rare and unique articles in painting, statuary, typography, and natural productions for nearly forty years, and had amassed a chaotic variety of strange and queer specimens, to which the livestock of Noah’s ark would have formed no parallel. Among this labyrinth of oddities, there were some valuable specimens of statuary, a few fine paintings, and a very considerable number of books, which from their rarity and costliness would be considered a precious acquisition by the bibliographer. Every fine morning, you might see a crowd of unwashed amateurs, gazing at the show window, when some new attraction was being displayed, and edifying each other with aesthetic criticisms as whimsical as the object of their attention. The sudden decease of Mr. Colman, which took place in the midst of his curiosities, he being found dead in a private room occupied by him in the building, brought this singular collection under the hammer.”

I’m still on the fence as to whether dropping dead in the midst of your own curiosities is an enviable end or not. The writer reports that after eight straight days of auction, Colman’s shop still left behind “a multifarious, fragmentary mass of odds and ends, sufficient to set up any number of country museums.”

Let it be stated that Pixie Smith never set foot in her great-uncle’s curiosity shop or met her industrious grandparents, as they had all died before her birth in 1878. Why then, this narrow investigation of her notable American relations? I think different readers will glean different understandings from this detailed look at Pixie’s Colman lineage, according to their own ideas of what traits may be passed down from family, and how. Perhaps some will recall the old adage that children often reflect their grandparents’ generation more than their parents’; does Pixie Smith’s involvement in the atavistic Golden Dawn movement make her an “antiquarian” like her great-uncle William? Did the power of her Tarot card illustrations flow from her Colman grandparents’ thriving trade as early American book illustrators? As someone who has performed a fair amount of ancestor work, I know that we don’t have to know our ancestors in life in order to unconsciously live their stories. What I notice in Pixie’s American lineage is the prevalence of “founders,” bold souls who threw off convention to brave new worlds and to pave the way for burgeoning cultural forms. Pixie clearly favored her pioneering Colman ancestors, standing as she does at the origin point of Tarot as a popular art form. However her father, Charles Edward Smith, seemed to follow in his father’s enterprising footsteps when he moved his small family to Jamaica to build railroads.

The Blackness of Pamela Colman Smith

Pamela Colman “Pixie” Smith was born in London on February 16th, 1878, to Charles Edward Smith and Corinne Colman Smith. When she was ten years old, her father, an artist by temperament but manufacturer by trade, took a job in Jamaica. In 1893, Pixie enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn to study art. After her father’s death, she waved good-bye to the Americas for good and moved to the United Kingdom in 1900, where she would settle permanently. Between 1888 and 1900, a period of twelve years, she spent extensive periods in both New York and Jamaica, sometimes considering one place her primary residence, sometimes the other. It would be thin soup indeed to argue that Pixie is “American” because she took her education stateside, and I don’t intend to do so. I am in fact much more interested in Pixie’s Jamaican experience, which seemed to have had the greater influence on her, as we shall see.

Here I want to qualify my use of the term “American” for the purposes of this blog as inclusive of the “Americas”: North, South, Central, and the Caribbean. We can name certain themes that are central to the identity of all these locales, such as: European colonization, the suppression and genocide of indigenous populations, and the importation of African slaves. Though the ratio of these ethnicities varies throughout history and across the grand geographical scope of the Americas, we can characterize “American” identity in the early period as the confluence of European, indigenous, and African cultures. Though obviously, white colonizers held social and financial power, and often violently suppressed Native American and African folkways, American identity was forged from the syncretism (as well as the clash) of these cultural groups.

The indigenous and African influence on American identity is a truth I take for granted. Almost 30 years ago I enrolled in a Native American studies college class while I was still in high school. One of the scholarly books we read at the time detailed all the cultural forms that contemporary Americans owe to Indian innovation, from the structure of our government to our cash crops. I later specialized in African-American literature when I was studying for my Masters, and took away the truth that American culture is black culture. In spite of virulent and persistent racism against black people, black culture has been widely adopted by white Americas. We only need to scratch the surface of American popular music to isolate one example of this blending of cultures. The appropriation of black styles by white musicians was in place long before Elvis - the most influential songwriter in the 19th century, Stephen Foster, rose to prominence as a minstrel performer of “Ethiopian Melodies.” I don’t have space to be exhaustive here, so am sharing just a few chance thoughts in service of a broad claim: the unique identity of Americans was created from the meeting and merging of African, European, and indigenous cultures.

While I’m sure our current obsession with “cultural appropriation” is well-intentioned, many critics have pointed out that culture has always been and always will be syncretic, formed by the “mixing together” of discrete traditions. We see countless examples of cultural syncretism across world history occurring between oppressor and oppressed. Perhaps the classic example of syncretism is Haitian Vodou, in which the Catholic saints of European colonizers became blended with the Yoruba pantheon of African slaves. It is the nature of people to share cultural traditions like food, music, art, dance, stories, and gods. We don’t stay in our lanes. This is not to say that there are no instances of cultural appropriation, or no power dynamics to consider when trying on another’s tradition; I simply wish to make the point that evolution and exchange are primary features of any culture.

A first edition of Pamela Colman Smith’s Annancy Stories.

The context of syncretism vs. cultural appropriation is necessary if we are to understand Pamela Colman Smith’s deep and decades-long relationship to Jamaican culture. In 1896, Smith contributed two tales of Jamaica, written in the African-derived patois dialect, to the Journal of American Folklore (she was 18 years old). In 1899, she published Annancy Stories, an expanded collection of West Indian folktales that included her original illustrations. After her move to England in 1900, Smith regularly performed the Jamaican folktales in dialect at private salons. The performances were so successful that she soon began to treat story-telling as a viable career path, advertising her services in print and appearing before paid audiences in the UK. On return trips to the United States, she delighted audiences with her humorous portrayal of a native Jamaican story-teller. In Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, the writers claim that Smith kept up these Jamaican performances in some form through World War I. It thus seems fair to infer that Jamaican culture was a dominant interest of Smith’s for about thirty years, from her West Indian childhood to her charity performances of “Annancy Stories” during the war. Her investment in A.E. Waite’s Tarot project was comparatively less, occupying, it seems, no more than a year of her time.

While it pains me to write this and will pain many others to read it, we can view Smith’s West Indian performances as a type of minstrelsy. I plan to heap some mitigating historical context on that claim, but the bare facts are there - if someone wanted to dismiss her as a culturally appropriating black impersonator, they could. Promotional photographs for her performances depict her seated informally on the floor, presumably in the pose of a black story-teller, wearing a costume that is out of step with the corseted Edwardian fashions of the day. Previously I had thought that Smith was just doing the early 20th century version of “bohemian” with her look, but the heavy beads and head wrap point to a self-consciously West Indian styling. I’ve never seen another white woman of the period outfitted similarly. While there is no record of Smith performing in blackface, I’ve used the term “minstrel” to call attention to the fact that she participated in the once-very-popular American entertainment of white people mimicking black speech and affect.

Pamela Colman Smith with some of the simple wooden dolls she used for telling her “Annancy Stories.”

Before attempting a more nuanced understanding of Pixie Smith’s performances of Jamaican folklore, I have some additional issues to raise. No doubt because of her enthusiasm for African-derived culture and dress and her upbringing in Jamaica, many casual observers have assumed that Smith was of African descent. There appears to be no evidence for this claim. Previously I outlined Smith’s elite American ancestry, and her family kept the same elite company after taking up residence in the British colony. Pixie’s friends were the daughters of the U.S. Consul in Jamaica, and the Smiths frequently entertained the governor and other prominent men in the colony’s leadership. Former slaves made up over 90% of the island’s population at the time of Smith’s birth, and emancipation had only been in place for roughly forty years. In Pixie’s trips to New York, she was placed under the care of a “Jamaica Negro nurse.” Thus it seems that Pixie Smith enjoyed the life of a colonial elite in Jamaica. However, it’s also clear that she possessed a measure of rustic freedom, and was able to make independent trips around the island with her horse and buggy.

Thomas Nelson Page, infamous today as a Southern apologist and writer of stories that reminisce about the good ol’ days of black slavery, wrote the introduction to Smith’s Annancy Stories. While we can’t infer from this fact that Smith shared Page’s retrograde political outlook, we can conclude that the book’s publishers at least felt Page was an appropriate authority to comment on Smith’s contribution to the genre of “negro folk-lore literature,” as he calls it. And from here on out, things just get more confusing. Page makes explicit comparisons of Smith to Joel Chandler Harris, writer of the popular Uncle Remus stories featuring the trickster character, Brer Rabbit. You may have no idea what an Uncle Remus story is since, after all, you’re alive in the 21st century. But I’m willing to bet that you’ve ridden Splash Mountain at Disneyland - you know, the ride with all the singing happy animals that seems uniquely unconnected to a Disney film and its accompanying merch. Except that it is - the film Song of the South was first released in 1946, a mix of live action and animation based on the Uncle Remus tales. The racist assumptions of the film are so obnoxious that it has never been released for sale on home video. I’ve always heard that it was the NAACP that blocked the film’s release, but Snopes denies this, and includes a statement from a folklorist about how the Disney film is more egregiously racist than the Joel Chandler Harris frame story.

The Two of Coins for The American Renaissance Tarot. Here we’ve used the pain on William Wells Brown’s face to dramatic contrast with the happy-go-lucky role he was made to play as a slave. The hare represents the Yoruba trickster character that got translated to “Brer Rabbit” in the United States.

From the differing receptions of the Uncle Remus stories over the last century, we gain much valuable context for placing Smith in the history of African-American folklore. Joel Chandler Harris was a white man who collected African-American folktales on a Georgia plantation. He felt “his humble background as an illegitimate, red-headed son of an Irish immigrant helped foster an intimate connection with the slaves” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joel_Chandler_Harris ). Here it bears pointing out that Pamela Colman Smith’s elite American background prevented her from collecting the folktales of former slaves from at least a relative position of social equality. While Harris was a lower-class member of American society and Smith came from an upper-class American family, both these collectors of African-American folktales were white. Much of the controversy surrounding Harris and his Uncle Remus stories revolves around the question of whether white writers can accurately and sensitively portray African-American folktales.

I’m sorry to inform you that I have no settled opinion on this issue, even with the benefit of a PhD in American literature. There are black intellectuals on both sides of the Uncle Remus debate, some who believe that Harris preserved an authentic African-American tradition in print, and others who think that the Uncle Remus tales will only ever be an index of white cultural hegemony. Like I said, it just gets more confusing from here. My personal sense is that whether we’re talking about race, religion, or culture, valuable observations can be made from both insider and outsider perspectives. When it comes to white writers representing black folklore, important factors to consider are whether the white writer has an attitude of respect, reverence, and appreciation for his subject, or an assumption of cultural dominance? These things are not so easily separated and can also co-exist; a prejudiced folklorist might still make valuable contributions to his field, and in fact most of the historical record is rife with this particular problem. The historians of every generation must always grapple with the previous generation’s ignorance. Pamela Colman Smith is the first known writer to represent Jamaican patois in print. She introduced the world at large to Anansi, an African-derived trickster figure who was both man and spider. Surely she deserves some recognition for transcribing a Jamaican oral tradition that may otherwise have been lost to history. Yet if you’re of the camp that believes only black writers can speak authoritatively about black traditions, then I can’t justify Smith’s book of Jamaican folktales to you.

Here it seems helpful to point out how class difference hampers the collection of folklore. Zora Neale Hurston, an African-American writer who was educated by anthropologist Franz Boas at Columbia University, conducted numerous folklore collection trips in the American South and the West Indies. Though she was Southern-born, her New York education and shiny car put up a social barrier between herself and the working-class communities she sought to interview. She writes of her experience at a lumber camp in Florida, “I mentally cursed the $12.74 dress from Macy’s that I had on among all the $1.98 mail-order dresses. I looked about and noted the number of bungalow aprons and even the rolled down paper bags on the heads of several women”(Mules and Men, 1935). For Zora Neale Hurston, even being of the same race and background as her interview subjects did not erase the class barrier inherent in a situation like the observation and collection of “culture.” So it’s difficult to imagine that Pamela Colman Smith, an upper-class white teenager, could magically transcend the rigid class structure of a former slave colony when interacting with black people.

One of Smith’s illustrations for Annancy Stories. For more click here.

A friend suggested that I explain away Pamela Colman Smith’s problematic racial impersonations as “belonging to a different time.” I’m not sure I want to do that; I feel pained when I read accounts of her morphing into “a strange African deity” during her performances of Jamaican folktales (PCS: The Untold Story 14). She herself described her story-telling technique as “Jamaican mammy style”(73). A 1906 reviewer named her “the champion narrator of dusky folk-lore,” and then went on to specify that her act moved beyond mere black “impersonation” to a more authentic “portrayal.” We know that Smith’s performances had a comic element, because it was reported that she made New York audience member Mark Twain “laugh like a child” (71-72). I don’t find it very satisfying to dismiss her minstrel act as “not racist” simply because it took place a hundred years ago.

I do, however, think it’s possible to acknowledge that Pamela Colman Smith’s black impersonations were disrespectful to people of African descent, and at the same time to understand that Smith’s heavy investment in black culture was the most American thing about her. And I don’t mean to imply that racism and cultural appropriation are key components of American identity, although some of you will be perfectly comfortable with that conclusion. Rather, I think that Pamela Colman Smith’s identification with black culture, to the point of her being moved to represent it on stage, is a function of the great-great-great-great-great-great-grand-daughter of colonial founders coming to terms with her Americanness and all that that bloody legacy entails. I am reminded here of the controversy surrounding Rachel Dolezal, a white woman who successfully passed as black, and who used that African-American identity as a ladder to social and professional preferment. At the time that the scandal around Dolezal’s identity broke in 2015, an academic colleague and I had a very long conversation debating whether her racial masquing might be homage; because it wasn’t caricature, and it didn’t further oppression, since Dolezal used her position as president of her local NAACP chapter and as Africana Studies college professor to actively support black people.

While I can’t say that Pamela Colman Smith improved the situation of West Indians with her book of folklore and impersonations of a Jamaican story-teller, I can say that her immersion in African-derived folklore in the Americas made a powerful statement as to the value of black culture. For an upper-class white woman in fin de siècle America, championing the unique forms that African culture took on American soil was an extraordinarily bold and controversial thing to do. More than anything else that Pamela Colman Smith ever did, redeeming the cultural contributions of the most oppressed people in the Americas precipitated her class descent from Mayflower daughter to improvident bohemian. In other words, representing the voices of black people in print alienated her socially from other young women in her class, and was surely not a route for preferment from the various branches of her elite and enterprising American family. American industry up to that point had always depended on the labor of a black underclass, whether directly or indirectly, and humanizing black people in any way, as Pamela Colman Smith’s folklore collection did, posed a threat to the white cultural hegemony.

Understanding Smith’s contributions to the field of black folklore is a challenge in 21st century America, where black voices gain mainstream recognition in previously off-limits spaces such as the high-cultural worlds of literature and art. It’s difficult to propel our imaginations back to a time when a black person would not have been allowed to appear on a stage like the one where Pamela Colman Smith performed her West Indian folktales in New York for an elite audience. At that time, black cultural expressions were seen as an affront to white dominance, unless they could be marshaled as evidence to prove the superiority of white cultural forms. When Zora Neale Hurston, a black woman, claimed and celebrated the folklore of African Americans in the 1930s, the old model of white commentators looking imperiously down on black “primitivism” was turned on its head. Yet Hurston caught fire from other black writers who believed in a more assimilationist path to social equality; Richard Wright was outraged by Hurston’s depiction of “happy darkies” under the oppressive American social system, which rigidly segregated black and white and left only the dregs of the American dream for black people. According to Wright, the colorful dialects and quaint folkways of black people smacked too much of slavery days, and did not represent the path forward to their inclusion in modern American life.

Writer and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston

Ultimately, Hurston’s ground-breaking collections of black folklore in the American South and the West Indies were out of step with mid-century ideas of racial progress, and her fortunes fared hard in the Civil Rights era. Once the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship and the toast of black Harlem, Hurston died unremembered and was buried in a pauper’s grave in Florida in 1960. The African-American novelist Alice Walker later went on a pilgrimage to find Hurston’s unmarked final resting place, and called out Zora’s name to entreat her spirit’s assistance in determining the right spot for a grave marker. Walker writes about this quest to redeem her literary foremother in her 1983 book of essays, In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens.

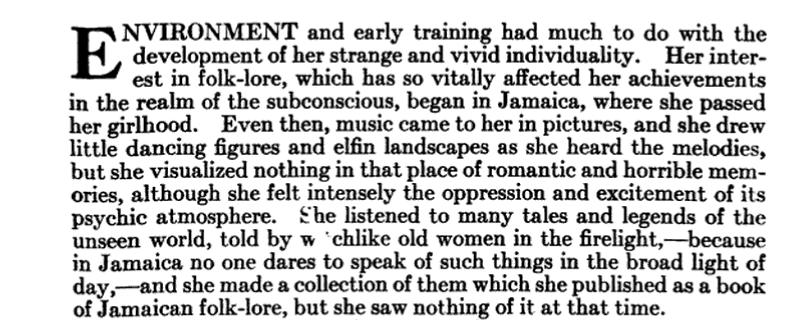

I wanted to include the obscurity of Hurston’s final years, her lost legacy, because it reminded me so much of Pamela Colman Smith’s final decades. Smith died penniless in Bude, Cornwall, in 1951, and was also buried in a pauper’s grave. Stuart Kaplan and Mary Greer, two of the authors of Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, have both undertaken pilgrimages to Bude to search out the site of Smith’s unmarked grave. Hurston worked closely with Franz Boas, the prominent anthropologist who edited the Journal of American Folklore where Smith published her first “Annancy Stories” in 1896. Perhaps my comparison should end with that oblique connection, since we know that the teen-aged Smith could not have made the formal, sustained recording of black folklore that Hurston did, in spite of her horse and buggy! Smith’s folklore collecting seems to have been limited to listening to “witchlike old women in the firelight” (The Craftsman, 1913), and we must wonder how much freedom this elite daughter was given to befriend black people in the socially repressive 1890s.

Image of the paragraph in the Craftsman magazine describing Pamela Colman Smith’s exposure to Afro-Jamaican culture.

I am still struck, however, by how two pioneering female collectors of black folklore in the Americas, one black and one white, both met such ignoble ends. Are we as Americans uneasy about black folklore because these African cultural survivals remind us of the trauma of the Middle Passage, and of the idyllic home from which the slaves were ripped? Or does taking black folklore seriously mean, on some level, taking black people seriously? And most importantly, was Pamela Colman Smith giving voice to the voiceless with her Annancy Stories, or was her adoption of the Afro-Jamaican dialect a clear case of the white privilege to culturally appropriate the underclass? Yes - to both? And also - gods if I know, and can I get an actual folklorist to weigh in? I believe these are questions best worked out in community and with the benefit of a diversity of voices.

I don’t want to back away from the discomfort I feel in Pamela Colman Smith’s problematic racial performances. I do want to argue that Pamela Colman Smith’s immersion in black folklore represents one way of contending with America’s twin shames: colonialism and chattel slavery. Listening to the stories of the oppressed, honoring them in print as a unique syncretic art form, and then acting them out with your body in the United Kingdom, colonialism’s very stronghold - are one way of making acknowledgement of African experience in the Americas. Identifying with America’s shadow class, as Pixie did, in however superficial or incomplete a way, point to her being a more astute American than her upper-class family members.

Epilogue

From her elite colonial pedigree and her family’s shaping role in American art and letters, to her own book of Annancy Stories, in which an African trickster figure outwits the forces of oppression, Pamela Colman “Pixie” Smith embodies the American character. Her Tarot illustrations have captivated viewers for over a hundred years, to the point that we may call them representative of the form. To deviate from the RWS template as a Tarot artist is to risk not having your work understood as Tarot. Trying to fathom Pixie Smith is a lot like gazing at one of the Tarot cards she illustrated; each person will see something different, and take away a private meaning intended just for her. It’s high time we understood the historical forces that created such an enduring and enigmatic artist, and one of those forces is, without doubt, Pamela Colman Smith’s American provenance.