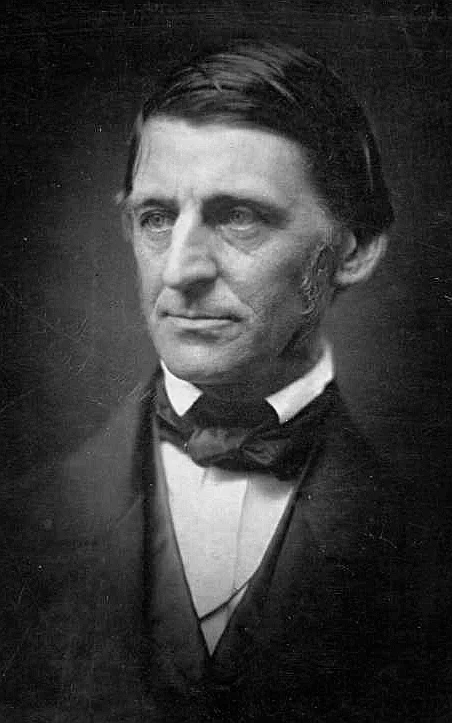

Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1857

When I first conceived of The American Renaissance Tarot, I knew that the Magician of the deck would be Ralph Waldo Emerson. The truth is that I've always struggled mightily with, and against, Emerson, and like to joke that when I dropped out of graduate school (the first time) it was because of the Emerson seminar. How do you come to terms with a figure so universally beloved, one whose influence has been so unimaginably vast? Not only was Emerson the lion of the Transcendentalist movement of the 1830s and 40s, he also inspired the careers of Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman. He transformed American philosophy and religion and his writing spurred on latter-day philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche. He was the venerable “Sage of Concord," a voice of comfort and wisdom for the Americans who flocked to his lectures from the 1840s through the Civil War era.

Detail of Emerson's desk in the Magician card for The American Renaissance Tarot

In a world so shaped by Emerson's thought, it can be difficult to grasp his unique appeal for Victorian-era Americans, even with the aid of retrospection. I often feel when reading Emerson similar to how I feel when watching Citizen Kane: bored, frustrated, confused by all the hype. I understand intellectually that Emerson was as much a revelation in his times as Citizen Kane was in 1941, but I still struggle to appreciate the artistry. I wrestled with these issues in that ill-fated Emerson seminar I took as a first-year English graduate student, and earnestly tried to understand what role Emerson fulfilled for his community, what service he performed. His role didn't seem to be religious, or so I assumed in those early readings of his work. I've never been convinced that he was a philosopher – whatever theoretical ground he lays out in an essay will be covered over with flowers by that essay's end. He's certainly no comedian. Why then, did he have such a devoted following in 19th century America?

If Emerson were writing today, would we classify his works as “Self-Help"?

When the answer came to me I was compelled to blurt it out to my colleagues in the Emerson seminar: “Self-Help," I announced, with all the assurance of a seasoned book-shelver at Borders. An uncomfortable feeling of mortification filled the room, and those who would meet my eyes offered only the gentle, kindly smile we reserve for the extremely stupid. No doubt that awful moment was what led me to pull up stakes and walk away from my graduate career, because it caused me to feel that I didn't belong within the temple of literary criticism; I had failed to understand something vital about Ralph Waldo Emerson.

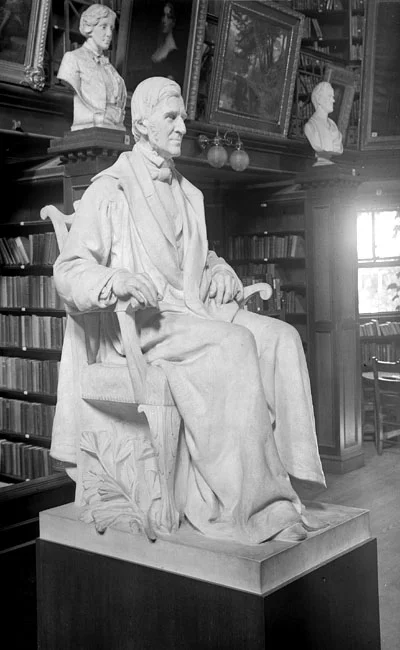

Sculpture of Emerson by Daniel Chester French

Of course I didn't really think that Emerson anachronistically performed the role of a 20th century Self-Help guru for a 19th century audience whose religious sensibilities had yet to be transformed by Darwin and Freud. And yet, when I returned to graduate school to pursue the entwined history of the Self-Help and New Age movements, I learned about the latter-19th century craze for “New Thought," whose originators had taken their first cues from – Ralph Waldo Emerson. So in trying to understand an old thing (Emerson's popularity) by correlating it to a new thing (the Self-Help industry), I had inadvertently stumbled upon the Transcendentalist roots of the New Age. Now when I read Emerson and hit that inevitable frustration point with his self-assurance, his philosophical reductionism, his retreat into glib and polished prose, I simply take him in the same spirit I would Wayne Dyer or Marianne Williamson and – I understand Emerson.

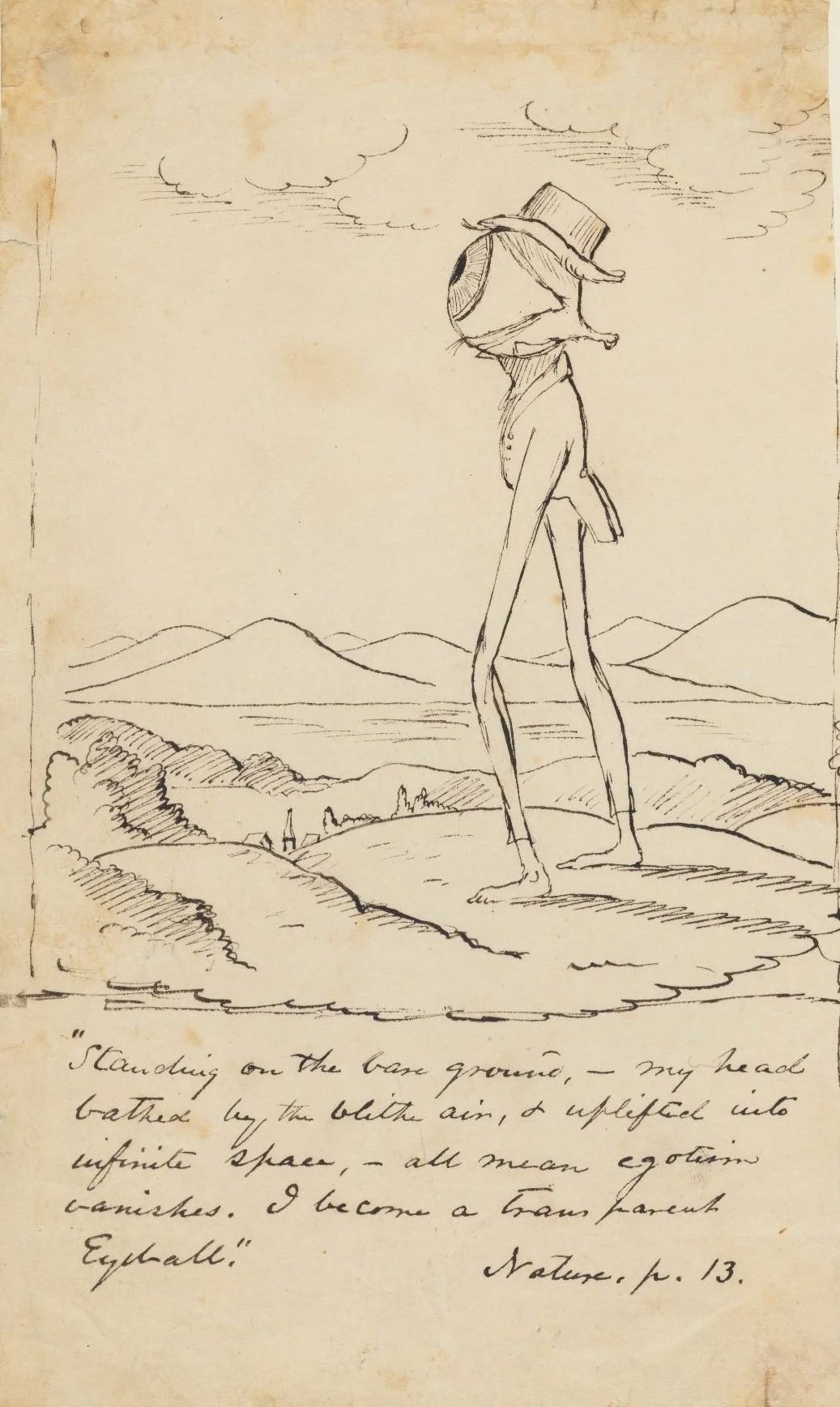

Spoof of Nature's “transparent eyeball" by Emerson's friend, Christopher Cranch

For the card image of the Magician I wanted to commemorate Emerson's 1836 book, Nature, the text that first gave definition and coherence to the budding Transcendentalist movement. By far the stand-out image of the text is Emerson's claim to be a “transparent eyeball," a phrase which sounded as odd and funny to 19th century ears as it does to us today. Emerson's friend, the poet Christopher Cranch, even spoofed the image in a cartoon which we've incorporated into the Wheel of Fortune for The American Renaissance Tarot. Consider the phrase “transparent eyeball" in the context in which Emerson used it and see if you can understand why the passage suggests the archetype of the Magician:

In the woods, is perpetual youth ... In the woods, we return to reason and faith ... Standing on the bare ground, my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space – all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God ... I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty.

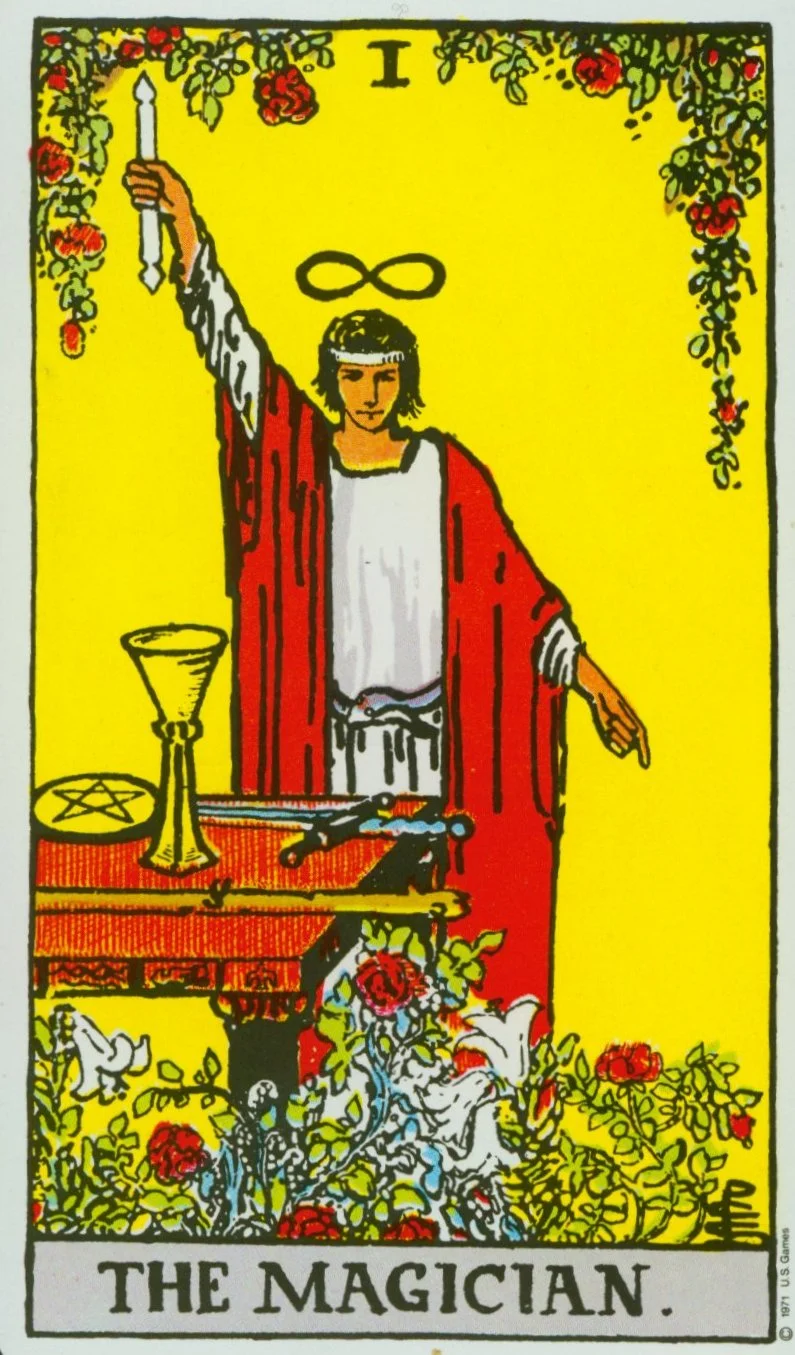

The Magician of the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot

In unpacking what Emerson means by all this, I could write a book, and many more learned critics have done just that. So instead, I'll just make a few notes to point you in the direction of further reflection. Emerson enters into this expansive consciousness while standing outside, much like the Magician depicted in the classic Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot. He describes being an exquisite seer, and how the dross of his human ego and personality have fallen away so that he can experience the pure perception of a god. Elsewhere in Nature Emerson claims that examples of men acting upon nature with their “entire force" are rare and the sole result of reason, which he defines as “an instantaneous in-streaming causing power." Because many people will be unfamiliar with this deployment of the word “reason," I offer my interpretation: the faculty of reason is a reflection of the mind of God, and when we yoke our human understanding to the transcendent reason of God, our results will be of an exalted character – truly magical works.

The Magician Aleister Crowley posing with the tools of his art

For those of you who think Magicians are just fictional characters out of medieval lore or hucksters trained in sleight-of-hand, all of this will sound a bit strange. For those of you who identify consciously with the Magician archetype through the Tarot or other extant occult systems, much of what I've written above will intuitively make sense. The Magician's art is to keenly grasp the laws of cause and effect, and to bridge the human Will to the “instantaneous in-streaming causing power" of divine mind. That reason is intimately connected to magic is no surprise to practicing Magicians, and the longtime association of the planet Mercury with the Magician card of the Tarot offers ready evidence of this fact.

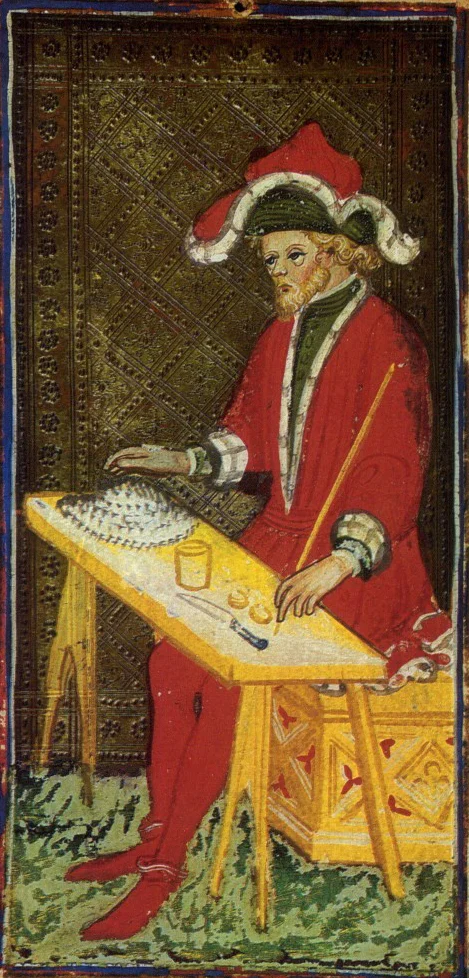

The Magician for the Tarot de Marseille, an influential deck that may have originated as early as the 15th century.

Mercury is the planet that represents intellect, communication, and perception in the various branches of the Hermetic arts. Mercury is also famously the patron of thieves and liars, and all those who manipulate with “magic words." In French the Magician card is called Le Bateleur and so preserves early associations of the first Tarot trump with jugglers and other tricksters. Ralph Waldo Emerson, born under the Mercury-ruled sign of Gemini, seems to embody the warp and woof of Mercury's meanings: incredible verbal fluency and erudition on the one hand, and shallow treatment of Big Ideas (done up in very pretty prose!) on the other.

The seated Magician of the Visconti-Sforza Tarot

Most importantly for a literary Tarot deck, Mercury is the planet that signifies writers and their craft. As such, the Mercury card, the Magician, has an elevated place within this project, and I wanted to be sure that our Magician depicted Emerson in the act of writing. I felt a little funny about this, since a seated Magician did not seem to make as powerful a statement as the iconic figure we know from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot. Yet I was keenly aware that although Emerson was standing with his head in the clouds and his feet on the ground when he first became a transparent eyeball, he must have been seated at a desk when he later recalled this transcendent moment and committed it to the page. The surrealist image Celeste conjured captures this dual experience, the writer's godlike perception and creative faculty, and the humble, sedentary reality of the literary craft and its implements. I was delighted when my friend Michael Pearce directed me to his article on the first Tarot Magician, the seated Magician of the Visconti-Sforza Tarot, whom he proves was a scholar by analyzing the items that appear on the figure's table. Thus I unconsciously performed homage to the earliest Tarot Magician by making the intuitive link between Magicians and writers. Incidentally, Michael's gorgeous Tarot-themed exhibit, The Secret Paintings, will be on tour this year; I present his Magician to you below.

The Magician, by Michael Pearce

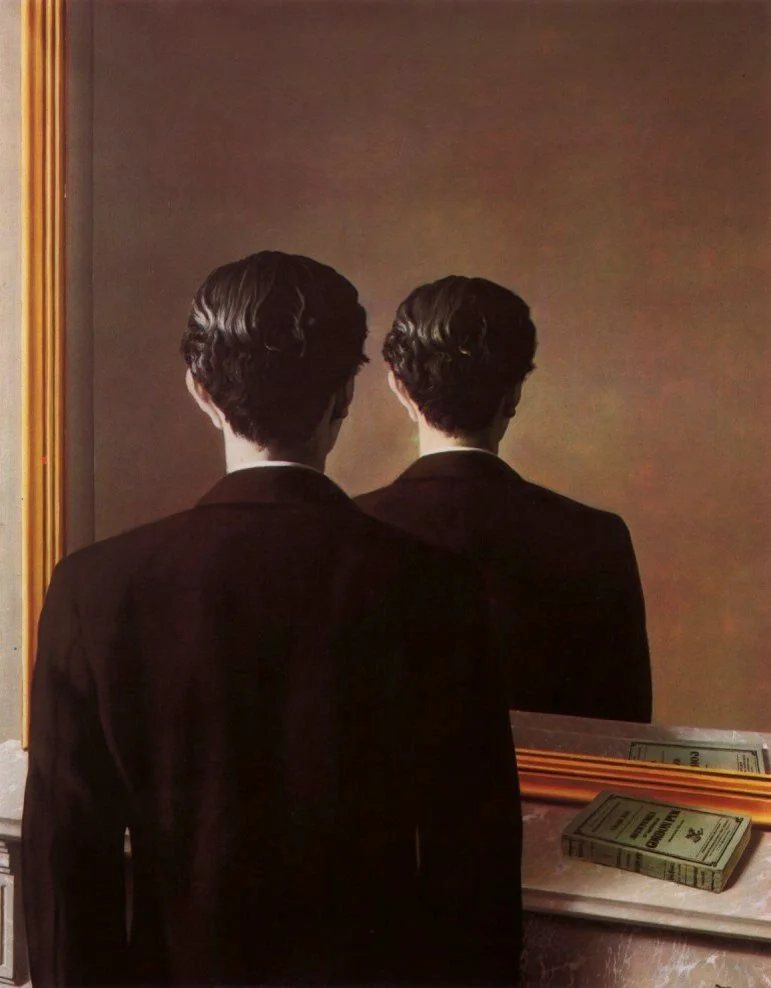

Not to be Reproduced by Rene Magritte, 1937, one of the visual inspirations for our Magician

As far as Emerson's gaze being directed at the vista instead of at the Tarot card viewer, I wanted the image to convey that the transcendant state Emerson achieves in Nature is available to everyone. Of course Emerson does not have quite as famous a mug as Lincoln or Poe, whose portraits appear in our deck, but the intent in showing you the back of Emerson's head was to emphasize his experience of “an instantaneous in-streaming causing power" more than his fame. And as Emerson writes later in the “Spirit" chapter of Nature, his experience may be imitated; you may try it for yourself.

Know then, that the world exists for you ... Build, therefore, your own world. As fast as you conform your life to the pure idea in your mind, that will unfold its great proportions.

Hopefully I've manged to explain here how it is that a former Unitarian minister, one who tended to look down his nose at the occult, actually makes the perfect Magician for The American Renaissance Tarot. The benefit of a project such as this is that there are as many Emersons as there are readers of Emerson, and so I encourage you to build, therefore, your own interpretation, in whatever manner the great Sage of Concord speaks to you.